I started these Reflections because I felt that the art histories I’ve read

left too much out, especially things relevant to photography. In the first article I talked about the evolution of our three brains: reptilian, mammalian (visual) and neomammalian (verbal), each with its own intelligence. In the second piece, I pointed out that from the beginning people have valued visual objects where something in the actual world made its own image, a good description of photography, even before its literal invention. This piece explores the impact of the word-oriented civilization on the visual arts,

a not always friendly relationship.

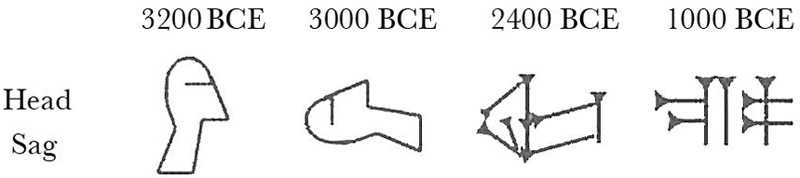

Recorded history—civilization itself as some would have it—began in Iraq, ancient Sumeria. I would guess that it was women who realized that just as pregnancy was not magic, vegetables came from seed. Agriculture produced surpluses, which produced commerce. Images were used as seals indicating ownership on the urns, which stored the surplus products. Words were invented to track the details of trade contracts and to do accounting. The letters started as pictures of actual things whose names were like the letter’s sound. These glyphs slowly evolved into abstract forms that still bore some resemblance to the original images:

The evolution was caused by technology itself. The early writing was done with a stylus, a pointed stick, used to scratch marks in clay tablets. Straight lines were quicker and easier than the curved lines of the first, curvaceous drawing-like attempts. Drawings, graffiti, had been the only “permanent” communication.

Unfortunately, wealth spawned a breed of big, bad tough guys who undertook one of the oldest rackets: “protecting” the new wealth and the people who produced it. They walled in the cities and civilization was born. The nomadic hunter-gatherers became traders, slaves or marauders on adjacent cities—state-sponsored armed robbery. It was at this point in our evolution that the neomammalian, verbal brain began to extend its characteristic dedication to control perception beyond self into political power, controlling others. The control effort was extended even to the visual arts and gave them a “purpose” – so that the rich and powerful could brag, indoctrinate and intimidate.

Myths deal with the unwritten history of human evolution; the stories were preserved in folk tales like Cinderella and passed down verbally as sung poetry. They were first written down in Sumeria.

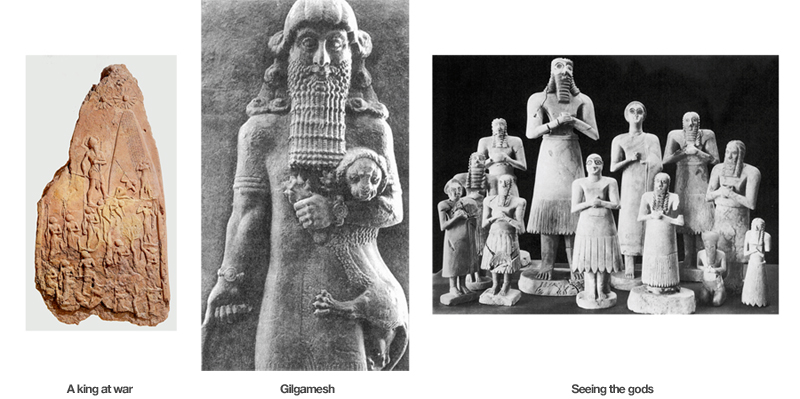

Gilgamesh was an historical king in Babylonia around 2700BCE. The epic myth about him was the first written story, inscribed on clay tablets around 2000BCE. Part of its theme is the transition from the paleomammalian, or visual, to the neomammalian, or verbal consciousness. Its first line is “He who has seen everything, I will make known to the lands.” The myth claims of Gilgamesh that “two-thirds of him is god, one third of him is human,” born of “the goring wild bull.” However, although “wise to perfection, [he] struts his power over the people like a wild bull.” Gilgamesh hears of a wild man, Einkidu, who “ate grasses with the gazelles and jostled at the watering hole with the animals.” Einkidu symbolizes the paleomammalian, animal visual brain. Gilgamesh sends a harlot to seduce him so the “animals, who grew up in his wilderness, will be alien to him.” The two men fight at first when Gilgamesh tries to exercise his droit de seigneur and bed a local virgin bride. But then the two men become close, have some mythic adventures, like cutting down cedars in Lebanon and resting in a jewel-dripping, amber-oozing forest. However, when Einkidu is killed, Gilgamesh panics, realizing he too will someday die. He sets off on a quest for immortality, but, drunk on beer, sleeps through his chance, crying out:

“For whom have I suffered?

I have gained absolutely nothing for myself,

I have only profited the snake, the ground lion.”

[The reptilian and paleomammalian brains? The transition to verbal dominance was not an easy one.]

Gilgamesh’s epic ends with him showing off the baked clay tablets on which his myth was written. The steles stood at the gates to his city for all to see. This first written bit of literature turns out to be, at least in part, political propaganda. On the other hand, the myth is remarkable in its honesty in describing the homosexual love between Gilgamesh and Einkidu; no don’t ask, don’t tell here. But also, symbolically, an effort to integrate the personality: thought and feeling, word and image. Ironically, Gilgamesh himself was illiterate, couldn’t read his own PR and died before the myth was written.

These ancient gangsters knew they were only men so, to shore up their power in addition to claiming godhood, they also turned to the priests, of course, and to artists, primarily sculptors. One king posted a massive mythical lion in front of his palace; several commissioned sculpted memorials to their marauding. These did not celebrate the bravery of the regular soldiers or mourn their deaths; the dictator/kings are the largest figures and take all the credit for the killing.

Wealthy people paid the priests for statues of themselves “seeing” the gods. The statues vary in size according to price, another indication of wealth and social status. This priestly cottage industry of selling boons, indulgences and dispensations from church laws, helped cause the Protestant Reformation a few thousand years later. That the wealthy show off their riches by buying “useless” objects is another tradition that continues. Visual artists can thank their stars for that.

The early rulers of civilizations, the power elite, seized on art’s ability to depict the unseeable, the mythic, the propagandist and the lie.

This first era of the neomammalian, the verbal brain, also produced the first written law code, the Hammurabi, to protect the weak from the strong, it was said. The laws were inscribed on baked clay steles. However, the lower classes were punished more severely for crimes against the upper classes than the opposite, setting a tradition still present in the law today. Laws are also evidence of the attempt by the conscious verbal mind to control the other brains transformed into the attempt at its very inception by the rulers of society to control their subjects.

The subjects consisted of “free” men, serfs and slaves. Most of the early civilizations were predatory, warring on neighboring city/states and bringing back wealth and slaves, oil and “guest” workers in today’s parlance. This tradition also persists today.

The Egyptians

It’s one of the loveliest ironies of art history that despite all their elaborate rules for art, the most famous piece of Egyptian art is Tutankhamen, King Tut. It is, after all, a death mask made by Tut’s face itself. And it doesn’t follow the rules. It’s not in profile, a major rule.

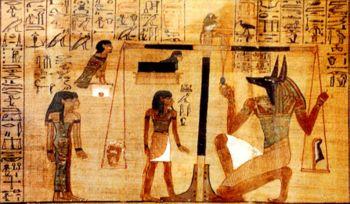

With the mummies, Egyptian culture inadvertently created a spectacular integration of many of the themes and purposes of art since the handprints in the prehistoric caves: the effort to escape time, to escape death. Egyptian priests promoted the idea that a person would be condemned to eternal wandering without its body to preserve the Ka. Continuing Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality and the Jericho death mask practices, Egyptian priests created an elaborate rite and technology for preserving the bodies of those rich enough to pay for it. The body was wrapped in several linen sheets and then decorated with a painted or gold gilded plaster death mask. The Pharaoh’s then were buried in the pyramids, extraordinary sepulchers in their own right. Sometimes in an over-the-top extravagance with mummies of their favorite pets.

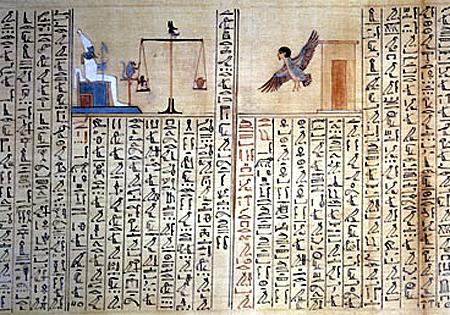

The audience for the art was not the people of the society, as in Sumeria, but the gods or even the dead kings themselves. To impress the gods to be met in the afterlife and let them know how important the mummy in the tomb had been in society, the paintings and sculptures were buried with the rulers they depicted. Sometimes along with the Pharaohs’ wives, children and slaves. Paintings on the tomb walls depicted everyday scenes, like the cycle of the seasons, to entomb the mummy in an endless cycle the same as his life. Art had a purpose. Although its purpose does seem a wee bit obsessive – crazy actually.

By the time Egypt became a power, visual objects as the baubles of wealth had become a firmly entrenched tradition in art. But “who pays the piper, calls the tune.” The verbal brain dictated elaborate rules about how to depict the powerful, in profile, for example. The sexes were differentiated by color; scale indicated social class or status. Every one was shown in profile.

Hieroglyphs, the Egyptian writing style continued to refer to the actual world; the letters look like birds and hands, lions and lips. The scribes were writing with brushes on papyrus, so curved lines were easy. Technology, the mechanical ability to do something, has sparked major changes in image making and its theories over the centuries.

From this era came Moses’ tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. They were more democratic than the Code of Hammurabi—the commands applied equally to all—and contained a similar if shorter list of things to do and not to do. Strikingly, for the history of art, one of those commandments forbade realistic images:

“I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt,

out of the house of slavery; you shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself an image, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and the fourth generation

of those who reject me, but showing steadfast love to the thousandth

generation of those who love me and keep my commandments.”

Maybe the ordinary people of Moses’ time had grown tired of the relentless self-promotion of the rulers and their art. They certainly were well aware of the inequities of class: the first recorded appearance of the Cinderella fable was in Egypt, in which a Pharaoh fell in love with a slave girl. Maybe they were tired of all the formal rules governing the painters, which we call Egyptian “style.:” Perhaps Moses understood the hubris of the artist who thought himself a god-like creator, or like Pygmalion, fell in love with his images and wanted them to come alive.

I think Moses could sense the inherent conflict between the visual and verbal brains. He is, after all, a character in the Bible, which starts “In the beginning was the word and the word was with God and the word was God.” His verbal brain here tried to kill off the image, the expression of the visual brain. Don’t confuse me with what you see, with the evidence of the senses, listen to my theory, read my lips, my concept. This conflict persists through the history of art, even to today. To some extent, visual artists can offer a corrective to the inhibitions and limitations of the verbal brain.

www.actualityinc.com