More than anyone, Andre Kertesz defined the aesthetic method of 20th Century photography by adding the instant, the vital moment, to vision, the classical point of view. And he has insisted from the beginning that his is a photographic vision: even as a youth he refused a suggestion he tint his prints, preferring the simple glossy photo to artful toning.

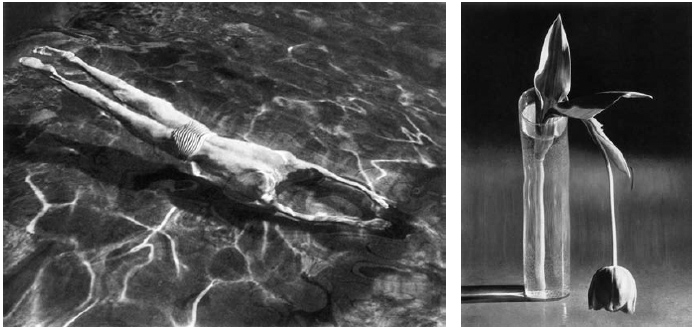

But even through the bulk of his work is pristine in method — just aim the camera and shoot — his curiosity and energy have driven him to extend the range of acceptable subject matter and propelled him past purism to experiment with distorting surfaces, still life assemblages, even to collage as in Disappearing Act and the Washington Square Mandala. But it is particularly in his direct abstractions that time and vision combine to achieve spatial ambiguity, allegory and an almost physical delight for the wandering eye.

His life’s work is like a pair of interlocking hands: it starts with an outward, documentary vision of the world: life in Esztergom and Budapest, service as a lieutenant in World War I, a journalist in Paris. But the tickle of abstraction, the first distortion of the Underwater Swimmer was joined in Paris by the funhouse distortions of nudes and the Melancholy Tulip, but particularly by the new (in the 1930’s) possibility to use the shutter to stop the world’s flow to achieve ambiguous compositions.

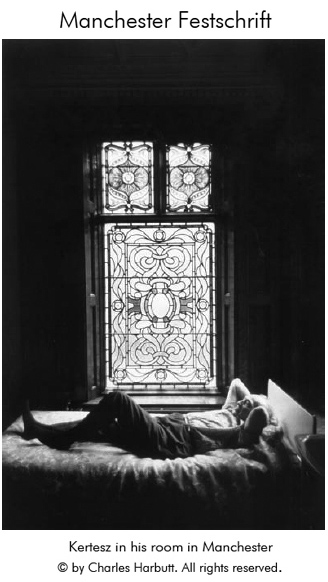

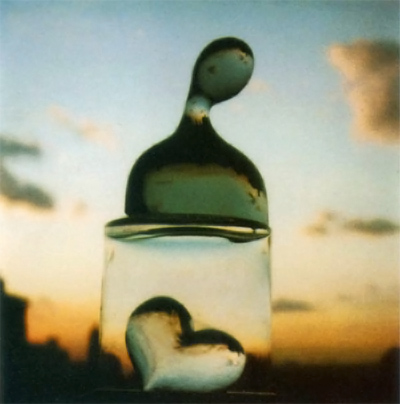

This evolution was harshly encouraged by his American refuge. Forbidden as an enemy alien to photograph freely, suppressed by an upper-class establishment just earning their own spurs and shocked by his wit and freedom, his energy and range misused by the fashionable media, Kertesz reacted with typical strength and vigor, extending his vision to produce the remarkable set of New York abstractions. When age and muggings made street photography dangerous, he looked out of his window onto Washington Square, then slowly withdrew into the apartment itself for the remarkable (and now colorful) series of recent still lifes. In safer climes, he continued some outward documentary work, but he seemed now more interior, the vision inward, completing the circle.

Kertesz was once the prince of Paris; in America he fell into oblivion and hardship. But eventually he came up again: books, exhibits, interviews, new work and honors crowded his life. The Legion of Honor and citizenship in Paris, an honorary degree, certificates from New York’s mayor, littered his work desk. “I never took a picture to win a prize,” he would remind younger visitors. But even more satisfying than the justice and decency of his autumnal world fame is that his work itself has always, even in adversity, been enveloped in charm and acceptance — even when he confronts pain and the inevitability of death itself. Viewers are hard put to find a depressed or dreary picture. “Attitude is a choice,” Andre says, and I suspect that it is this that has brought him our love.